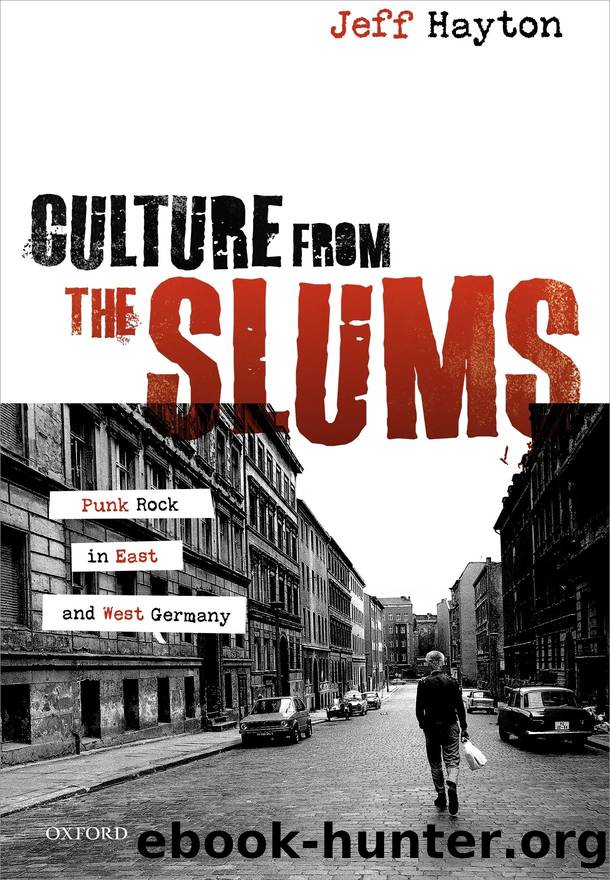

Culture from the Slums: Punk Rock in East and West Germany by Jeff Hayton

Author:Jeff Hayton [Hayton, Jeff]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780192635853

Publisher: OxfordUP

Published: 2022-02-08T00:00:00+00:00

Conclusions

As 1983 dawned, the NDW seemed unstoppable. But just as quickly as it inflated, the bubble burst. In early 1983, a ruinous Extrabreit tour foreshadowed the coming catastrophe. Embarking on a thirty-three-date tour throughout West Germany in which the band hoped to see several thousand people per show, only twenty-six thousand fans attended their first twenty-eight concerts.155 While in 1982, 48 percent of songs placing in the charts featured German lyrics, in 1983, this percentage dropped to 28 percent.156 In January 1983, amidst declining readership, Sounds merged with MusikExpress and many of the journalists moved to Spex which became the countryâs most innovative pop culture magazine.157 As Hornberger notes, DÃFâs song âCodoâ in September 1983 was the last NDW song to reach number 1 in the German charts: in October 1983, there were no NDW titles in the top 20 for the first time in two years.158 As demand shriveled up, ZickZack and independent record stores like Rip Off found themselves sitting on product they could not move. After the success of Andreas Dorauâs single âFred vom Jupiter,â ZickZack had pressed fifty thousand copies of his debut LP Blumen und Narzissen (1981). Except the album was a flop, and Hilsberg and Maeck were stuck with tens of thousands of unsellable records.159 In August 1982, with Hilsberg drowning in red ink, ZickZack collapsed, as did the important independent distributors Eigelstein and Boots.160 In 1983, also massively in debt, Maeck was forced to close Rip Off.161 And while the NDW limped on for a few more yearsâmostly in name only as Nena illustratesâthe irony and realism that punk had supplied were gone and the genre became a caricature of what it had once been.

The incredible popularity of the NDW created a crisis in West German punk. Its meteoric rise, its media-driven spectacle, and its dramatic fall, all seemed to point to its innate artificiality. That long-time rockers rebranded themselves as NDW before quickly ditching it seemed to invalidate the genre. Its success meant the institutions and values which had organized punk needed to be redefined, and for many punks, the experience proved that the boundaries of subcultural legitimacy had grown too porous. That the media had played a large role in the rise of the NDW was a black mark against the genre since television and star-culture were perceived as artificial, a means of selling copy and viewership rather than genuine musical interest. Paradoxically, as a consequence of NDW success, West German punk was increasingly ghettoized as the more musically conservative vision of Hardcore came to define the genre. As the NDW evolved, it ceased to share a historical trajectory with punk as the former became its own genre of popular music, and the ties that held them together unraveled.

Contemporaries and more recent observers have often attributed the demise of punk to the actions of the music industry: as Diedrich Diederichsen has suggested, the âcreative worldâ surrounding German punk was destroyed through the âimmense onset of commercialization.â162 Certainly, the association of profit and superficiality is a well-established trope in histories of popular music.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13673)

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11831)

Diary of a Player by Brad Paisley(7577)

Assassin’s Fate by Robin Hobb(6216)

What Does This Button Do? by Bruce Dickinson(6207)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(5804)

Altered Sensations by David Pantalony(5103)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5007)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4197)

The Death of the Heart by Elizabeth Bowen(3620)

The Heroin Diaries by Nikki Sixx(3548)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3308)

Beneath These Shadows by Meghan March(3307)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3268)

The Help by Kathryn Stockett(3146)

Jam by Jam (epub)(3090)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3073)

Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing: 20th International Conference, CICLing 2019 La Rochelle, France, April 7â13, 2019 Revised Selected Papers, Part I by Alexander Gelbukh(2995)

Strange Fascination: David Bowie: The Definitive Story by David Buckley(2872)